Finding a first job in a time of crisis

Geneviève Houriet Segard, Doctor in economic demography, Head of studies at EDHEC NewGen Talent Centre, and Manuelle Malot, Career Director and NewGen Talent Centre discuss in an article originally published on The Conversation of the job search.

The slowing of the global economy due to the Covid-19 crisis will affect the entry of young graduates into the job market from autumn 2020. This is not the first recruitment crisis France has seen.

In fewer than 30 years, three major depressions have undermined the labour market. Geopolitical in 1993, technological in 2000 and financial in 2008, these crises made the entry of young graduates into the labour market more difficult during each period.

So that their experiences might shed some light for young graduates today, we talked to former students of the CentraleSupélec and the EDHEC Business School, who faced an unfavourable labour market at the time of looking for their first employment. How did they approach job-seeking in such difficult times, and were their careers affected over the long term?

More proactivity in times of crisis

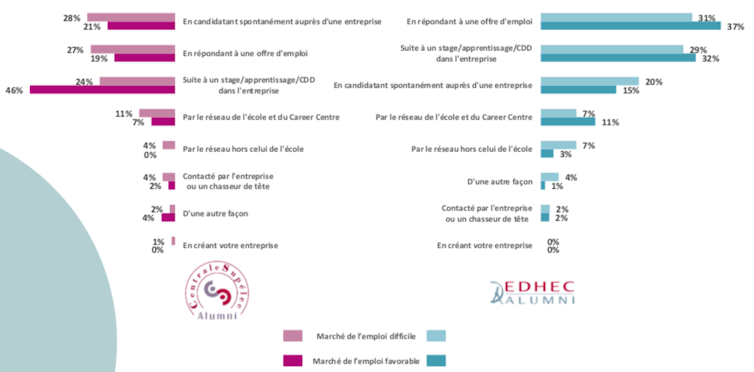

According to our results, when the labour market is favourable, 39% of graduates get their first job following an end-of-study internship, an apprenticeship, or a sandwich course (46% of responses from engineers at the CentraleSupélec and 32% of graduates of the EDHEC) (cf. figure 1).

But in an unfavourable labour market, an internship less often leads “naturally” to a first position, and job-seekers must adopt more proactive strategies in crisis periods.

Systematically responding to general job offers, valuing all experiences acquired during one’s studies, making numerous unsolicited applications, and mobilising graduate networks are the most effective job-seeking tactics.

Indeed, in periods of crisis, 29% of young graduates who participated in our study found their first job by responding to a job advertisement. Among CentraleSupélec students, the largest proportion of them got their first employment following an unsolicited application.

A former EDHEC graduate seeking their first job during a recruitment crisis stated:

“In the summer of 2015, there was a mini-crash on the financial market, which totally blocked recruitment in finance departments. By applying for jobs and making unsolicited approaches, I was lucky enough by December to have a choice among four permanent contract offers.”

A former CentraleSupélec graduate, who ended up finding a job quickly, described a

similar pathway:

“At the end of September, beginning of October, at job-application time, most job market offers had disappeared (a worsening of the effects of the post-9/11 crisis). Despite that, I applied to the companies that I had chosen (either through job advertisements or by making unsolicited applications). I had just one positive reply to that first series of applications (5 or 6 of them). I had interviews in October and November; the position was exactly what I was looking for, with a salary slightly below what I was hoping for.”

This upheaval in the usual job-seeking hierarchy confirms company reluctance to hire during moments of crisis. But it is always possible for young graduates to find their first job if they are proactive in their searching.

Flexibility and adaptation are indispensable qualities

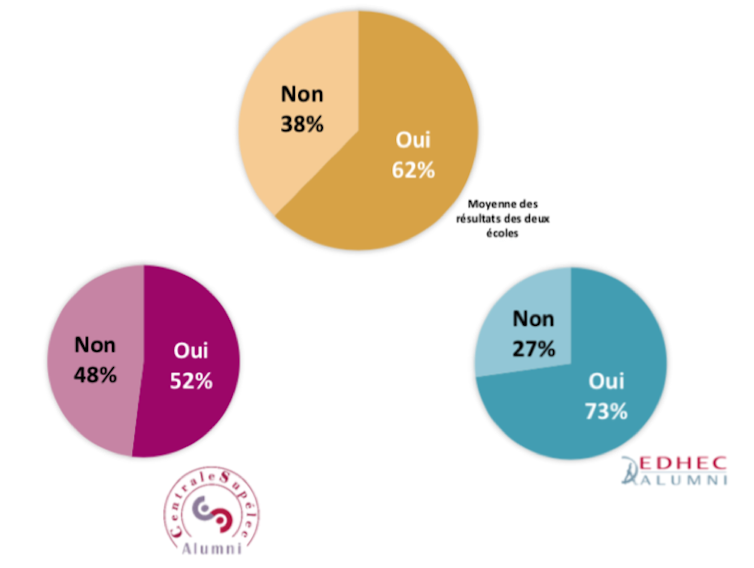

Among the graduates who participated in our study, 62% believe that entering the labour market during a time of crisis has proved that they can be flexible and can adapt to circumstances (73% of the EDHEC graduates and 52% of those from CentraleSupélec).

career?

A former graduate participant in the study stated:

“I changed direction and went overseas. With hindsight, that reorientation was difficult and took some time, but I also developed resilience and a capacity to adapt, which served me well during subsequent crises.”

Looking for employment in times of crisis has taught young graduates to adapt in the face of unanticipated circumstances. They have shown resilience and flexibility in broadening their searches to sectors not included in their initial projects. Sometimes, they had to do extra training or move abroad.

They have also had to demonstrate greater realism and energy, and to mobilise their personal and alumni networks more often. Some of them accepted moving to places they had not envisaged, staying in France instead of going abroad, or vice versa.

For one of the graduates, this was experienced as beneficial, particularly in terms of

relationships with managers:

“I am convinced that behind these challenges lay something to learn, something that helped us to grow; a bit tough, certainly, but it changed us. Going into the firm with a desire to learn and to prove that one merits the position presents a different “flavour” to our managers, and probably established long-term relationships of trust between us and our employers.”

Others augmented their training while waiting for better days. Being flexible about functions, contracts, and type of company, leaving the beaten path by applying for positions in little-known firms, and accepting salary compromises have all been useful tactics for finding a first job.

In the end, careers are not greatly affected

With hindsight, four in five CentraleSupélec and EDHEC graduates believe that their careers did not suffer from the initial difficulties of their first job searches.

Among the former students, only 21% experienced a slower start than expected, in a sector they had not initially targeted, or with a salary lower than anticipated. This reflects misplaced ambitions and thus the study remains reassuring because the majority ended up finding jobs.

In conclusion, the study revealed that crisis periods demand intellectual, physical, and psychological mobility. While such crises make entering the work force more difficult, in the end they have little impact on graduates’ future careers.

The advice that we can offer to young graduates looking for work in a period of crisis is to be proactive and visible while remaining alert to the opportunities.

As one of the CentraleSupélec graduates explained:

“Don’t be inactive while waiting for work. You must find an occupation (a personal project, volunteer work, acquire new skills, etc., which allows you to respond to the question that all potential employers ask when the situation improves, and they start hiring again: ‘What have you been doing since you finished your studies?’”

It means not only being methodical and using your networks, but also preparing for

interviews, defining your professional project, and demonstrating flexibility in your job-

seeking criteria.

This article was co-published with The Conversation France under the Creative Commons

licence. Read the original article.