Research tax credit: "nudge" or "sludge"?

In France, the question of non strictly monetary incentives for companies to develop R&D appears to be a central issue, but one that has been too little documented. Read this article by Pierre Courtioux, initially published in French in The Conversation.

In France, the question of non-monetary incentives for companies to develop R&D appears to be a central issue, but one that has been under-documented. To borrow from the concepts of behavioral economics, the question arises as to whether the research tax credit (CIR) is a nudge (i.e., a device in the interest of companies investing in R&D) or a sludge (i.e., a device that encourages companies to give up or abandon R&D due to its complexity), at least for some of them. To answer this and other questions, EDHEC has just launched the Observatoire de la R&D en entreprise (ORDE-EDHEC).

In a knowledge-based economy, corporate R&D is a strategic element in sustaining growth. The governments of many countries, aware of this challenge, are seeking to encourage its development by setting up various public support schemes for private R&D. In France, the research tax credit (crédit impôt recherche - CIR) is a central element in this panoply of schemes. It costs the French government around 6 billion euros a year, and enables companies to deduct 30% of the R&D expenditure declared under this scheme from their corporate income tax.

No powerful "multiplier effect"

The CIR does not always get "good press". It is not uncommon for the media to point the finger at abusive practices of R&D declarations to the CIR by companies whose "real" research activity may be questionable. Against this backdrop, we may well wonder, as EDHEC's economics department does, whether the CIR is not "a really false good idea", and whether it should not be put on the list of tax niches to be eliminated. But we might just as well ask whether, on the contrary, by doing so we run the risk of "throwing the baby out with the bathwater", and whether the intense media attention given to the "bad practices" of certain companies masks a more fundamental commitment to research on the part of many companies.

Studies show that one euro less in tax revenue only corresponds to one euro more in R&D expenditure. Ktasimar/Shutterstock

The conclusions of the recent report published by France Stratégie (Harfi and Lallemant, 2019), which synthesizes the results of several studies on the CIR commissioned as part of its evaluation by the Commission nationale d'évaluation des politiques d'innovation (CNEPI), indicate that the CIR has "achieved its first target: growth in R&D spending by its beneficiaries".

However, reading this report does not give the system a blank check. Indeed, the main findings of the studies, which confirm a number of studies carried out on the subject in recent years, are that, roughly speaking, 1 euro less in tax revenue only corresponds to 1 euro more in R&D expenditure. Against a backdrop of severe budgetary pressure, these results raise questions about the direction of public policy choices. If there is no powerful "multiplier effect" from the scheme, is it not in the State's interest to abandon the CIR and collect the tax directly, then finance public and/or private research through subsidies?

A "poorly calibrated" system

However, the relatively low impact of the CIR on research spending may also be explained by problems of general calibration and effective implementation of the system, which are currently poorly documented.

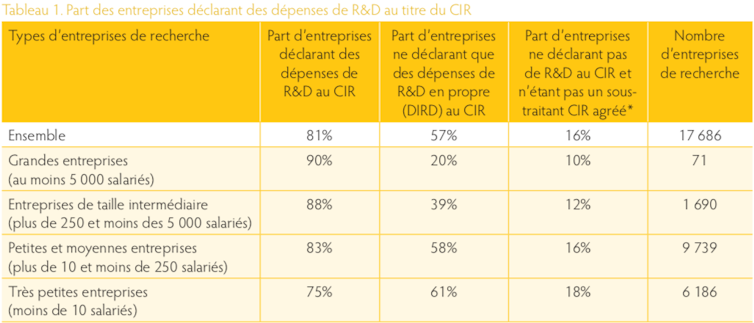

From this point of view, the recent study published by EDHEC (Courtioux et al., 2019) tends to show that the scheme is rather "poorly calibrated" and that it actually affects companies that do R&D in very different ways, if at all! In fact, this study shows that 16% of French companies that regularly carry out R&D do not make use of the scheme, even though they have actually incurred R&D expenditure during the year (see table below). What's more, companies that declare their expenditure under the CIR do not declare it in full, since the study estimates that 34% of R&D expenditure is not declared under the CIR.

Note: (*) Company in which none of its constituent companies is approved for CIR subcontracting expenditure. ERD 2013 (MESRI), GECIR (MESRI, DGFiP), calculs des auteurs.

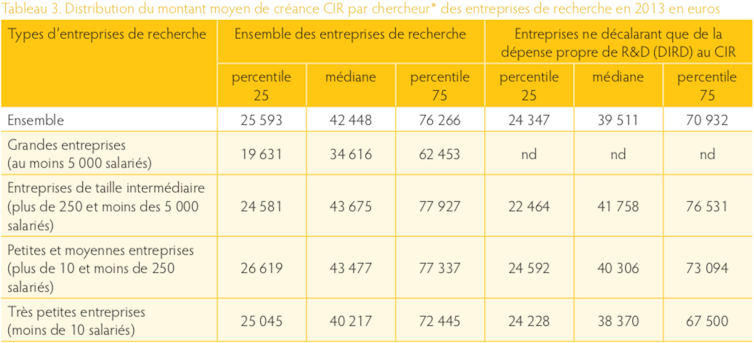

Some aspects of implementation, which the study discusses on the basis of an exploratory qualitative survey carried out by EDHEC students, may explain these discrepancies. Indeed, this part of the study highlights the existence of significant administrative costs, which can be explained by the need for a research project presentation document capable of convincing the tax authorities, and an efficient process for tracking internal R&D expenditure: you can't improvise a company focused on research! Added to this is the possibility of a compliance audit by the tax authorities, the difference between which and a tax audit (which it may in part herald...) is not always clear to small businesses. These factors can lead companies to be "cautious" in declaring their CIR expenditure, i.e. to declare less than they actually do... or even to declare nothing at all! However, the tax return that companies can expect from the CIR is not negligible: the study shows that the median claim per researcher is around 42,000 euros, and that for 25% of companies this amount exceeds 72,000 euros, as shown in the table below.

Note : (*) équivalent temps plein ; (nd) non divulgué afin de respecter les règles du secret statistique. ERD 2013 (MESRI), GECIR (MESRI, DGFiP), calculs des auteurs.

The dangers of poor anticipation

In addition, the study published by EDHEC shows that a proportion of companies performing R&D and declaring it for the CIR are not covered by the Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation (MESRI) survey, which serves as a benchmark for measuring total R&D expenditure at national level. In fact, some companies fall outside the scope of the survey, either because they only carry out R&D (and declare it as CIR) on a one-off basis, or because they have ceased trading (liquidation, etc.).

In the case of those who report "occasional" recourse to the CIR, it is difficult to know exactly why they have stopped claiming it. These companies may either have been discouraged by "compliance checks", or even "tax checks", but it may also be a case of poor anticipation of the administrative costs involved in declaring R&D expenditure as CIR. This poor anticipation may even put the company in jeopardy: relatively fragile start-ups may have serious difficulties in mobilizing the resources needed to cope with a tax audit! The authors of the study estimate that these are around 6,600 companies that "punctually" declared an average of €109,000 in R&D expenditure. But more than the amount of R&D declared, which falls off the radar of public statistics, it is the strategies of companies and their R&D practices, "good" or "bad", that are now important to understand in order to carry out a complete evaluation of the CIR.

Read the EDHEC position paper entitled "What is the return on the research tax credit? here.

This article is co-published with The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the article of The Conversation.