The Blackrock affair: some truths to set straight

Daniel Haguet, Associate Professor at EDHEC Business School, discusses the Blackrock affair in an article originally published on The Conversation.

On December 31, 2019, during the traditional civil promotion of the Legion of Honor, artists (Chantal Lauby, actress and former member of the Canal plus comedy group "Les Nuls", singer Gilbert Montagné, etc.), scientists (Gérard Mourou, Nobel Prize in Physics 2018)... and the Chairman of BlackRock's French subsidiary, Jean-François Cirelli, already a Knight of the Legion of Honor since April 2006, was promoted to the rank of Officer on the proposal of the Prime Minister.

Media coverage of this award (one of a total of 487!) triggered salvoes of criticism from political and union leaders. They argued that, in the current context of pension reform, this award would promote "funded retirement" and encourage pension funds.

Both questions are fundamental and need to be examined beyond ideological prejudices.

The French are already turning to capitalization

Traditionally, pension systems are divided into two categories:

- pay-as-you-go schemes, where contributions from current workers finance the pensions paid to current retirees. The balance of the system is based on the ratio of contributors to retirees, and the percentage of working people in the number of contributors. The pay-as-you-go scheme is a mutualized system. In France, it is by far the majority system;

- funded plans, which are based on individual contributions by participants, invested in financial instruments and paid out as a lump sum or a life annuity on retirement. The financial instruments used can vary widely: equities, bonds, etc.

While the pay-as-you-go scheme remains the bedrock of our pension system, it seems that the French have decided to supplement it with individual capitalization schemes, long before there was any talk of pension reform, for which BlackRock has been accused of lobbying.

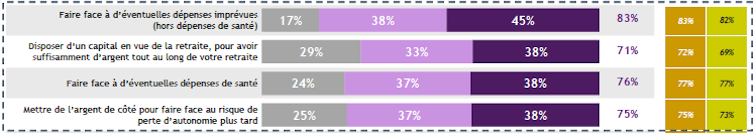

The latest AMF savings and investment barometer clearly shows that the proportion of our compatriots wishing to "have capital for retirement" rose from 69% in 2017 to 72% in 2018. In 2019, these French savers invested 144.6 billion euros gross in life insurance policies, of which 39.6 billion in unit-linked products, i.e. 27%, the highest percentage in years, despite the continuing decline in rates of return on euro-denominated assets.

The real issue, then, is no longer to worry about setting up individual retirement preparation schemes based on the principle of capitalization - they already exist. The real issue is to encourage them and facilitate their use by savers. This is precisely the aim of the Loi Pacte, adopted in 2019, which provides for the launch of new pension savings plans (PER) during 2020. These are supposed to offer greater legibility, more flexibility, or even more exit options.

BlackRock is not a pension fund

It's important to remember that the New York-based multinational BlackRock is not a "pension fund", but simply a company specializing in third-party portfolio management, whose financial products are distributed to their customers by private banks and insurance companies. BlackRock is also famous for its index management business, which seeks to match the performance of other major indices such as the Cac 40 or the Dow Jones. This explains, for example, why BlackRock is present in the capital of the majority of companies listed on the Cac 40.

Pension funds can take many forms. They can be public (as in the case of the famous CalPers fund reserved for civil servants in the State of California) or private. They may take the form of defined contributions ("401(k)" plans in the United States) or defined benefits. Tax and social security provisions vary from country to country.

An asset for the economy

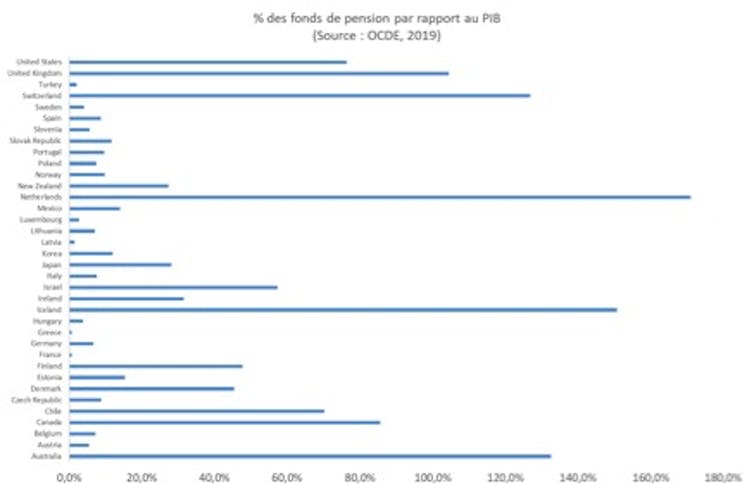

Many countries, both within and outside the OECD, have pension funds (see chart). It is interesting to note that the presence of pension funds in the economy is not confined to Anglo-Saxon countries, and that certain European countries such as the Netherlands and Switzerland are characterized by a very high proportion of pension funds in relation to GDP.

Are all these countries systematically wrong, or are pension funds really an asset for the domestic economy and financial markets? Academic research has studied the subject extensively, and the results are fairly conclusive. A 2003 study, for example, demonstrates the positive impact of savings institutions such as pension funds and insurance companies on domestic financial markets in a range of developed and developing countries.

The authors conclude that the presence of institutional savings does indeed increase the dynamics of financial markets, and thus the volume of equity and bond markets. This facilitates the financing of the economy in the broadest sense, since this is ultimately the role of financial markets: to enable the optimal allocation of financial resources.

It is perhaps not insignificant, moreover, that in July 2019 the European Union announced the launch in 2021 of the Pan-European Pension Plan, a non-mandatory individual financial product that will enable Europeans to save for their retirement...

This article is co-published with The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article on The Conversation France website.