The recovery will occur with young graduates or it won't occur at all

Geneviève Houriet Segard, Director of Careers and NewGen Talent Centre and Manuelle Malot, PhD in Economic Demography, Head of Studies at EDHEC NewGen Talent Centre discuss in an article originally published on The Conversation the economic recovery and opportunity for young graduates.

While some firms have profited from the confusion into which the world has recently been thrown, pursuing and even accelerating their recruitment, a more cautious majority have frozen recruitments and put off such decisions until the post-holiday return in September or until next January… which feels like an indefinite delay to a naturally impatient young graduate.

The labour market, which has been very favourable to young graduates for some years, has made the attraction, retention, and motivation of talent a major preoccupation of managers. For almost 10 years, firms have used considerable resources to recruit high-quality candidates.

Today, economic uncertainty reigns, but nothing has changed on the demographic level: higher education institutions do not train enough graduates to respond to the needs of global economies.

In addition, “stop-and-go” recruitment policies have demonstrated their long-term weaknesses. It is not in the interests of business to slow their relationships with higher education institutions or to stop recruiting.

Supporting young people in their search for meaning

In contracting, the job market will, of course, partially resolve the questions of attractiveness and loyalty among young professionals in companies, but the problem of commitment will, conversely, be more acute:

- young graduates who have the impression of having less latitude to choose their employer might not be very committed to their missions, especially if their expectations of social impact and utility are not satisfied; and

- the aspirations of these young people will remain the same or even be reinforced, so recruiting in difficult times should not exempt firms from thinking about how they play a societal role above and beyond simply running their business.

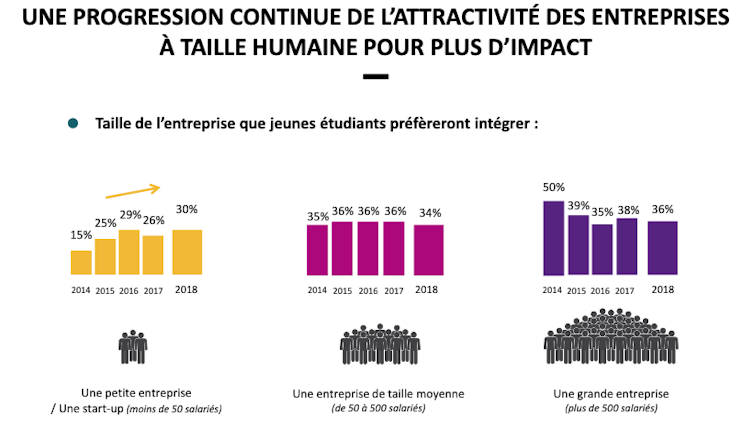

Over the past five years, the attractiveness of big companies has fallen, indicating above all a disaffection for the complexity of these types of organisations. The craze not only for start-

ups but also for SMEs (small and medium enterprises) – structures on a human scale –demonstrates the desire of young people to measure more easily the impact of their work and

to feel more like collaborators and agents than salaried employees.

(“How will the new generation transform business?”) by the NewGen for Good at the

EDHEC Business School (May 2019). Careers.edhec.edu

Young people’s desire to be useful, to have an influence in the firm, to participate in decision making, to have an impact, to make a difference, is an opportunity for businesses regardless of their size.

This need to be useful was strengthened during the spring-time confinement of graduates whose concern not to do “ bullshit jobs“ was sometimes muted by periods of unwelcome partial unemployment .

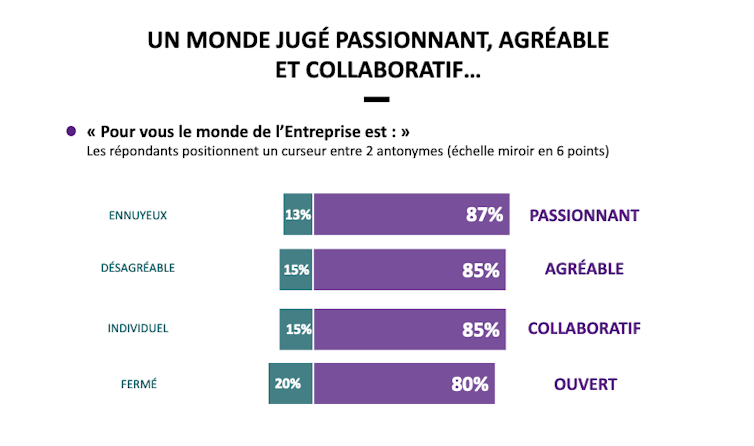

Because far from the stereotype of a young generation said to be “ disenchanted” by business, 87% of management students have a positive vision of it and are confident in the power of the firm to change the world. Indeed, they often put more confidence in business

than in political power.

Today, the company is expected to be a creator of meaning in place of other such creators–school, army, the Church, politics – which have been somewhat displaced.

Young people consider the firm as a motor of innovation, but is above all, for them, a place of collective adventure where they can surpass themselves. Therein lies the opportunity for recovery.

Doubts about the sincerity of the commitments

But while contemporary business might seem passionate, open, and collaborative to them, they are also not naïve in their judgements: the firm is not always fair, is often complex, and vertical.

It seems to reflect an old world, an overly complicated organisation, too hierarchical, restrictive without proof that the restrictions are efficient for collective performance or for individual growth.

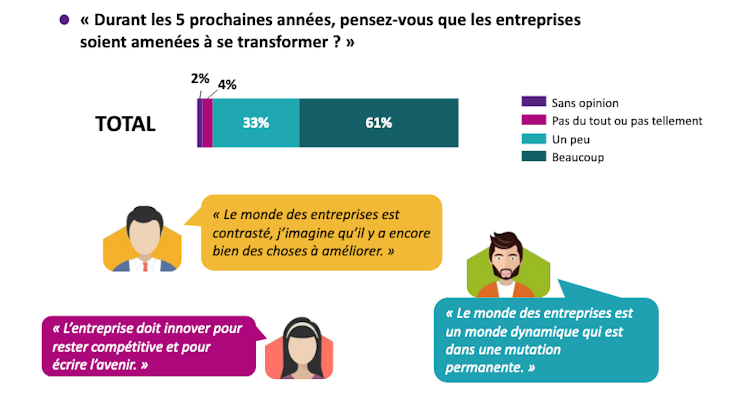

In addition, 61% of young people believe that the business is going to undertake a serious transformation, especially in areas such as relationships at work, the social responsibility of firms (RSE), and their ways of dealing with problems.

Before this spring, young people had a sincere but sometimes ephemeral commitment to the firm, rarely staying in their first position for more than two years.

NewGen for Good at the EDHEC Business School (May2019). Careers.edhec.edu

While crisis reduces the risk of ephemeral commitment, it might be revealed to be less than sincere. This is the management challenge for tomorrow: cultivating young collaborators around shared values and objectives.

For this new generation, success is no longer limited to staying loyal to their firms (only 3% think this way) but should be coherent with their values (58%) and ambition (16%).

Further reading: Management bienveillant et RSE : ce que les jeunes générations attendent de l’entreprise

Economic crisis does not let firms off the hook in this sense for young people. In their criteria for choosing to commit themselves to a particular company, first comes diversity and inclusion, followed by social and environmental responsibility.

Further, lack of contribution to the general interest is one of the deepest disappointments among young employees in their first job.

An Unprecented situation- and opportunity...

The younger generations who are joining the world of work have already begun to change some rules of the game to create a more sustainable business model.

We can cite, for example, the « Manifeste étudiant pour un réveil écologique », an emblematic initiative for this generation, signed by more than 32,000 higher education students, whose public questions succeeded in garnering 54 responses from directors of large businesses about their approach to social responsibility.

Firms have not been inactive in the face of this call for change: reducing the number of steps on the hierarchical ladder at Schneider Electric, integrating non-financial components in the remuneration of managers at Danone et le Crédit Agricole, etc.

Included in the Pact law, in addition to the integration of the RSE dimension in the social objectives of the firm is the possibility of including a specific purpose in a firm’s statutes, allowing it to define a long-term project that takes into account all of its stakeholders.

Thus, the Pacte Law’s invitation to redefine the place of business in the society and the aspirations of the younger generations for an economically sustainable world have sown the seeds for the emergence of a new kind of management that the current crisis might accelerate.

For some years, we have been theorising about a "VUCA " world – volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous – without imagining the extent to which the spring of 2020 would give us the chance to put it into practice. Firms were already looking for organisational agility but know now that it is no longer sufficient.

Some think that the virus is changing the rules of the game. Above all, it gives managers a chance to act.

This is a difficult moment, but one that is creating opportunities for change; for decision makers and companies, it is an opportunity to privilege social utility, to begin to develop a sustainable business model and to stop seeing the logic of performance as being in opposition to the logic of social responsibility. Recruiting young graduates is at present the surest way to get there.

This article is co-published with The Conversation Conversation under the Creative Commons licence. Read the article original.