Unemployment insurance reform: the temptation of universality

Arnaud Chéron, EDHEC Professor, discusses in an article originally published in French on The Conversation different conceptions of unemployment insurance depending on geography.

At a time when the debate on unemployment insurance reform in France is getting bogged down, it would seem useful to compare the systems currently in place in Europe. The task is a daunting one, since the degree of "generosity" of unemployment insurance, a term often used to characterize one system or another, covers a multitude of dimensions: amount, duration, degressivity, ceiling, eligibility conditions, criteria for sanctions in the event of refusal of an offer, to name but the main ones.

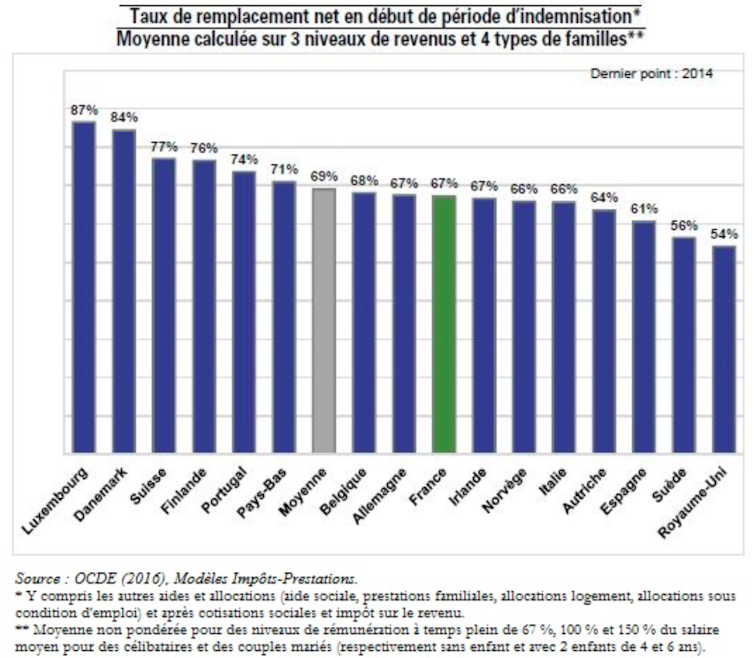

As a general rule, this generosity is summarized by a synthetic indicator: the net replacement ratio. This ratio relates the average income from unemployment (over a given period) to the previous income from employment. Reasoning in "net" terms emphasizes that not only unemployment benefit, but also all social transfers (housing and family benefits) are taken into account, as well as changes in taxation induced by the change in status on the labor market.

According to the most recent figures provided by the Direction Générale du Trésor (OECD 2016 data), France is on a par with the European average, with an average replacement ratio equivalent to 67% at the start of the benefit period. This figure is close to that calculated for Germany, higher than the 54% obtained for the United Kingdom, and three times higher than in the United States. However, this "average" ratio masks significant underlying heterogeneity, particularly in terms of family situation and previous income level.

In France, for example, the replacement ratio at the start of the period is not very dependent on family configuration, unlike in other countries such as Germany, and especially the UK, where familiarized benefits and tax credits are largely dependent on labor market status: the replacement ratio for a childless single person in France is 68%, compared with 66% for a single-earner couple with two children, with figures of 58% and 77% respectively in Germany, and 39% and 68% in the UK, with strong dependence on family structure in the latter two countries.

Different "philosophical" conceptions

On the other hand, France has the highest replacement rate for the highest-paid workers: 68%, compared with 59% in Germany and 32% in the UK (48% OECD average). For example, a single person without children in France can receive a maximum benefit of 7,130 euros, compared with just 2,450 euros in Germany, and 615 euros in the UK. Last but not least, the duration of benefit payments also differs substantially (two years in France, one year in Germany and six months in the UK), as do the conditions for eligibility: in France, you only need to have worked for four months in the last 28 to be eligible, and this 4/28 ratio should be compared with ½ in the majority of countries.

As you can see, behind the fairly similar average replacement ratios lie major differences in terms of compensation, one of the most glaring of which is certainly the absence of degression of the replacement ratio in France with the level of remuneration, contrary to what is observed in most other countries.

This echoes an almost "philosophical" difference in conception of the career risk coverage system: traditionally, the universalist approach adopted in the UK (known as Beveridgian, in reference to the work of the Englishman Beveridge in the mid-twentieth century, who promoted a principle of universality and uniformity in the assistance provided to the unemployed), which consists of guaranteeing a minimum income financed by taxation, the insurance-based approach (Bismarkian, in reference to the system initiated by German Chancellor Bismarck at the end of the 19th century), in which replacement income is directly linked to previous employment, financed by social security contributions and managed by the trade unions.

Universality and insurance

In the first case, the result is that high-paid workers see their income drop substantially when they lose their job, as benefits - although dependent on family structure - are very largely flat-rate. In the second case, as in France and Germany, the insurance logic predominates, with replacement ratios remaining very high for high-wage workers.

This fundamental questioning has finally been put on the table by the French government, which has moved towards a universal activity income. This proposal has recently been taken up by Medef, which is promoting, on the one hand, the introduction of universal coverage managed and financed by the State, and on the other, compulsory supplementary insurance piloted by the unions. It already follows the abolition of employee contributions to unemployment insurance, which is now effective and has changed the situation, with part of the unemployment insurance system now financed by taxation (CSG).

While unemployment benefit in France already incorporates a Beveridgian logic, with, for example, the specific solidarity allowance for the unemployed at the end of their entitlement, the question raised is that of the relative weight accorded to universality vis-à-vis insurance. Limiting indexation to previous salaries, increasing the flat-rate base of unemployment benefit, and/or reducing the ceiling on benefits, would have the effect of increasing the weight of the universal component, and therefore of redistribution, to the detriment of insurance.

From the point of view of economic efficiency, these options deserve to be discussed, since some of the workers likely to fall rapidly into an unemployment trap are precisely those with average incomes who, because of the high indexation to previous salaries, are in a position to refuse certain job offers (at the risk of seeing their human capital depreciate). As we can see, the issues at stake in a new reform of the unemployment insurance scheme are manifold, involving a juxtaposition of philosophical, political and economic considerations.

This article is the translation of the article initially published in French in The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Picture on freepik